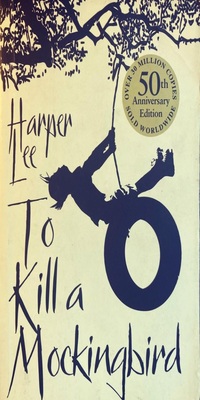

To Kill a Mockingbird: Summary, Plot, Characters, Literary Analysis & More

“To Kill a Mockingbird” is a novel by Harper Lee, first published in 1960. This Pulitzer Prize-winning novel stands as one of Lee’s greatest critical and popular accomplishments.

Set against the backdrop of a small town in the midst of the Great Depression, “To Kill a Mockingbird” delves into the intricate tapestry of social class, racial inequality, and human worth.

The narrative revolves around Scout Finch, a young girl, and her brother Jem, as they navigate the complexities of their town’s society. The enigmatic figures of Boo Radley and Tom Robinson become central to the story, emblematic of innocence wrongfully persecuted and the broader themes of prejudice and compassion.

As their father, Atticus Finch, undertakes the defense of Tom Robinson, an innocent black man accused of raping a white woman, the family grapples with the harsh realities of bigotry and injustice.

Amidst the mayhem, Scout’s growing realization of the world’s complexities and her evolving friendship with their mysterious neighbor, Boo Radley, drive the narrative forward. This introspective journey prompts readers to question societal norms and explore the multifaceted nature of humanity.

To Kill a Mockingbird Summary

“To Kill a Mockingbird” unfolds in a small Southern town during the Great Depression, focusing on Scout Finch and her brother Jem.

Scout’s father, Atticus Finch, a principled lawyer, defends Tom Robinson, a black man accused of raping Mayella Ewell, a young white woman. This trial becomes a focal point, highlighting the town’s racial tensions.

Scout, Jem, and their friend Dill are captivated by Boo Radley, a reclusive neighbor, and they embark on a quest to uncover his mysterious past. The narrative oscillates between their adventures and the trial. Despite Atticus’s compelling defense, Tom Robinson is unjustly convicted due to prevailing prejudice.

The book’s overarching theme of injustice is punctuated by the innocence of the metaphorical mockingbird—both Tom Robinson and Boo Radley are likened to this innocent creature, harmed by society’s biases.

Scout’s coming-of-age journey intertwines with societal issues, symbolized by the mockingbird motif.

Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” profoundly addresses racism, moral growth, and societal norms, providing a timeless critique of societal injustices and a testament to the enduring struggle for equality and compassion.

Set against the backdrop of a small town in the midst of the Great Depression, "To Kill a Mockingbird" delves into the intricate tapestry of social class, racial inequality, and human worth.

Table of Contents

Summary The Plot Characters Key Themes Genres Language used Literary devices Summing upThe Plot

In the town of Maycomb, Scout Finch (Jean Louise Finch) and her brother Jem befriend Dill and become intrigued by Boo Radley, a reclusive figure in the Radley House. Their father, Atticus Finch, defends Tom Robinson, a black man accused of assaulting Mayella Ewell, daughter of Bob Ewell. During Tom Robinson’s trial, it becomes evident that the evidence is against him due to racial bias.

Scout’s gradual realization of the injustices around her is juxtaposed with her fascination with Boo Radley’s mysterious nature. Boo’s reclusive behavior contrasts with Nathan Radley’s stern control over him. As the trial unfolds, Atticus strives to defend Tom Robinson, but the Finch family faces backlash from the town.

Ultimately, Scout and Jem are attacked by Bob Ewell as retaliation, but Boo Radley intervenes, saving them. The true nature of Boo is revealed, and Scout realizes the depth of his kindness. The novel centers on themes of racial prejudice, empathy, and moral growth, painting a vivid portrait of societal complexities and individual transformations.

Characters

Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” introduces a cast of characters that navigate the complex tapestry of a small Southern town. Each persona represents a facet of society, shedding light on the novel’s themes of justice, prejudice, and compassion.

Scout Finch (Jean Louise Finch)

At the heart of the narrative is Scout, an inquisitive young girl with a keen sense of observation. Her evolving perception of the world shapes the story’s lens.

As she befriends Dill and experiences her father Atticus’s moral stand, Scout’s transformation from innocence to understanding unfolds, mirroring the journey from ignorance to enlightenment.

Atticus Finch

Atticus, a principled lawyer, and father, embodies moral integrity. His commitment to defending Tom Robinson in the face of racial prejudice showcases his determination to uphold justice.

Atticus’s wisdom and guidance provide a foundation for Scout and Jem’s moral growth, emphasizing empathy and courage.

Jem Finch

Scout’s older brother, Jem, embodies the complexities of adolescence in a racially divided society. His initial fascination with Boo Radley matures into a broader understanding of the town’s biases during Tom Robinson’s trial.

Jem’s experiences parallel his transition from youthful naivety to a deeper awareness of societal injustices.

Boo Radley (Arthur Radley)

Boo Radley’s reclusive existence in the Radley House captures the town’s imagination. Despite his isolation, Boo’s small acts of kindness, such as leaving gifts and saving Scout and Jem, reveal the depths of his compassion.

Boo’s character encapsulates the novel’s exploration of appearances versus reality and the potential for redemption.

Bob Ewell

Bob Ewell represents the sinister underbelly of Maycomb’s society. His false accusations against Tom Robinson stem from a place of prejudice and hatred.

Ewell’s actions mirror the bigotry and ignorance that pervade the town, serving as a stark reminder of the destructive power of discrimination.

Tom Robinson

Tom Robinson’s character embodies the tragic consequences of racial bias.

Falsely accused of assaulting Mayella Ewell, he becomes a symbol of the racially motivated injustices prevalent in Maycomb. Despite his unwavering innocence, the trial’s outcome underscores the systemic inequalities of the era.

Mayella Ewell

Mayella, the daughter of Bob Ewell, epitomizes the intersection of power and vulnerability. Her false accusation against Tom Robinson reflects the desperation to preserve social hierarchies, showcasing the intricate ways in which prejudice manifests.

Dill Harris (Charles Baker Harris)

Dill’s arrival each summer brings an air of childlike wonder to Maycomb.

His fascination with Boo Radley fuels the children’s adventures, serving as a catalyst for their understanding of empathy and human connection. Dill’s presence underscores the novel’s exploration of childhood innocence and the power of imagination.

Key Themes

In “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee, numerous themes interweave to create a profound tapestry that examines societal complexities. One prevailing theme is the exploration of morality and empathy.

This is exemplified when Uncle Jack, Scout’s uncle, reprimands her for her harsh judgment of her teacher, illustrating the importance of understanding others before passing judgment.

Another theme is the power of a father’s influence. Atticus’s role as a widowed father shapes his children’s moral compasses. Atticus’s notes about the Ewell family and his agreement to defend Tom Robinson exemplify his dedication to righteousness, teaching his children the importance of standing up for justice.

The Halloween pageant, where Scout falls asleep in her ham costume, underscores the theme of innocence. As Scout inadvertently breaks Jem’s snowman, she grapples with the loss of innocence. Miss Maudie helps Scout understand that growth comes with the loss of innocence and the acquisition of knowledge.

Central to the narrative is the symbolism of the mockingbird. Atticus’s explanation to Scout that it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird reflects the theme of innocence and injustice. As Atticus stands against prejudice, he becomes an embodiment of the theme of moral courage.

Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” is a tapestry of interconnected themes, portraying the complexities of society through the lives of its characters. These themes resonate, inviting readers to reflect on their own understanding of empathy, morality, and the pursuit of justice.

Genres in To Kill a Mockingbird

Harper Lee defies easy categorization due to its multifaceted genres. Primarily a bildungsroman (a novel about the moral and psychological growth of the main character), it follows Scout Finch’s coming-of-age journey, capturing her growth from innocence to understanding in the midst of societal complexities.

The novel also encompasses elements of social commentary and legal drama, as Atticus Finch’s defense of Tom Robinson against racial prejudice forms a central plotline.

The book features elements of mystery, epitomized by Boo Radley’s enigmatic presence and his eventual role as a savior. This adds an air of suspense, enticing readers to uncover the truth about Boo and explore themes of perception and reality.

Furthermore, “To Kill a Mockingbird” incorporates historical and sociopolitical elements, serving as a reflection of the Southern United States during the Great Depression. Its exploration of racial prejudice and social inequality contributes to its historical relevance, creating a rich backdrop for its character-driven narrative.

The novel’s blend of genres contributes to its profound impact. By combining various narrative threads, Lee captures the complexity of human experience, providing readers with a thought-provoking and emotionally resonant exploration of moral growth, societal norms, and the enduring pursuit of justice.

Language used in To Kill a Mockingbird

Harper Lee’s writing style in “To Kill a Mockingbird” employs vivid language to evoke the story’s atmospheric nuances and emotional depths. Through a skillful interplay of narrative elements, Lee captures the essence of the characters’ experiences.

Atticus’s explanations and beliefs serve as beacons of wisdom, illuminating the story’s moral framework. The anticipation of Ewell’s revenge and the tension surrounding Scout’s brave stance showcase Lee’s ability to create a palpable sense of suspense.

Scout’s journey from starting school to exploring the Radley place with Jem showcases Lee’s talent for crafting imagery that immerses readers into the characters’ world. The night on which Jem breaks his arm while fleeing the Radley porch is infused with a sense of dark foreboding, masterfully enhancing the emotional intensity.

Aunt Alexandra’s presence and Atticus’s presentation of Tom Robinson’s case highlight Lee’s knack for character development and narrative pacing. The poignant scene where Jem carries Scout home, coupled with Judge Taylor’s house, epitomizes Lee’s use of settings to amplify emotional resonance.

In “To Kill a Mockingbird,” Lee’s language delicately knits together the plot’s intricacies and the characters’ emotional landscapes. Through her adept storytelling, she crafts an immersive experience, guiding readers through a tapestry of emotions against the backdrop of a Southern

Literary devices in To Kill a Mockingbird

In “To Kill a Mockingbird,” Harper Lee employs a masterful array of literary devices that contribute to the novel’s profound impact. Through vivid imagery and detailed descriptions, Lee brings characters and settings to life, immersing readers in the world of Maycomb.

The novel encompasses the Bildungsroman genre, chronicling Scout’s growth from innocence to understanding, echoing societal changes.

Lee skillfully utilizes foreshadowing to create suspense and anticipation, weaving a web of interconnected events. The narrative features various forms of irony, from dramatic to situational, shedding light on the complexities of the character’s lives and the town’s dynamics.

Symbolism is woven throughout, particularly through the mockingbird motif, underscoring the themes of innocence and injustice.

The author employs allusions and wordplay to add depth to characters and themes. Flashbacks provide insight into characters’ motivations and history, enriching the narrative. The presence of a mysterious neighbor, Boo Radley, serves as a metaphor, highlighting the theme of perception versus reality.

Pathetic fallacy, subtly mirroring emotions through the natural world, enhances the emotional resonance of the story. Harper Lee’s adept use of these literary devices creates a rich tapestry of narrative layers, fostering a timeless work that examines morality, empathy, and the intricacies of human nature.

Similes

This book employs similes to vividly illustrate characters and situations, enhancing readers’ understanding and engagement with the narrative.

For instance, the description of Nathan Radley as “a ‘man who’d done you a favor’ as openly as it was done by Miss Maudie’s large heart” illustrates his demeanor as a neighbor, while also revealing his underlying motives.

Likewise, Atticus’s observation that “most people are nice, Scout, when you finally see them” serves as a poignant simile, paralleling the gradual unveiling of societal truths and individual motivations. Comparing the Radley property to a “malevolent phantom” intensifies the air of mystery around Boo Radley and his dwelling.

When Boo asks Scout to “pull up the chair and come on in,” the simile underscores Scout’s tentative entry into his life, emphasizing the connection between the two characters. The metaphorical resonance of Jem’s pants caught in the Radley fence likens their entanglement to the broader complexities of the town’s prejudices.

Lee’s deft use of similes enriches the narrative by providing evocative comparisons that deepen characterization and atmosphere, ensuring readers’ profound immersion into the story’s intricacies.

Metaphors

Harper Lee masterfully employs metaphors in “To Kill a Mockingbird” to infuse deeper layers of meaning into the narrative. The own knife that Nathan Radley thrusts into the tree symbolizes his attempt to cut off connections to Boo Radley’s interactions with the outside world, reflecting the town’s efforts to isolate him.

The plight of Tom Robinson’s widow becomes a metaphor for the persistent injustices faced by the marginalized during that era. Her struggle serves as a microcosm of the broader societal biases.

Likewise, the mysterious Boo, the reclusive neighbor, functions as a metaphor for the fear of the unknown. As his true nature is revealed, he becomes a representation of misunderstood innocence, challenging the town’s prejudices.

These metaphors enrich the story by encapsulating complex themes, fostering a deeper understanding of societal dynamics, individual experiences, and the poignant messages “To Kill a Mockingbird” conveys.

Analogies

“To Kill a Mockingbird” employs analogies that serve as powerful tools for readers to grasp intricate concepts. Atticus’s notes on the Ewell family can be seen as an analogy for his meticulous examination of society’s ills. Just as he dissects the Ewells, his pursuit of justice involves dissecting the layers of prejudice.

When Atticus agrees to defend Tom Robinson, it’s analogous to his broader stance against societal biases. His agreement reflects a commitment to dismantling prejudiced norms, a sentiment echoed in the central mockingbird plot summary—the defenseless should not be harmed.

The way Atticus explains complex ideas to Scout and Jem parallels his role in explaining the complexities of morality and empathy to society. These explanations function as analogies for his larger role as a moral compass.

Furthermore, Atticus believes that people have both good and bad qualities, just as Boo Radley’s character is portrayed. This analogy underscores the nuanced nature of humanity, revealing that even reclusive figures can possess kindness.

These analogies enrich the narrative by providing relatable frameworks for understanding the intricacies of prejudice, empathy, and human nature. By bridging the abstract and the familiar, the novel invites readers to contemplate these themes in a more accessible and profound manner.

Imagery

Harper Lee employs vivid imagery that envelops readers in sensory experiences, enhancing the narrative’s emotional impact. The moment Ewell vows revenge, readers can visualize the intensity of his malevolent determination, deepening the sense of impending conflict.

The image of Scout standing in the Radley yard embodies a sense of curiosity and unease, painting a clear picture of her apprehension. When Scout befriends Boo Radley, the imagery captures her cautious steps toward understanding, evoking the emotional journey of bridging the gap between the unknown and familiarity.

Imagery is also used effectively during the scene with Heck Tate. His calm demeanor and authoritative presence are depicted through imagery, creating a vivid mental picture of his character and role in the story.

Lee’s use of imagery is particularly pronounced as Scout starts school and returns home, vividly portraying the contrast between the world of education and her intimate family life. The imagery surrounding Jem’s homecoming emphasizes the emotional impact of his return, resonating with readers on a sensory level.

Throughout the novel, Harper Lee’s skillful incorporation of imagery crafts a rich tapestry of sensory experiences, inviting readers to fully immerse themselves in the characters’ lives and emotions, while also deepening their connection to the story’s themes.

Symbolism

In “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee, symbolic elements seamlessly weave into the narrative, enriching the exploration of broader themes. Atticus’s notes serve as a symbol of his conscientious examination of social disparities, mirroring his role as a moral compass in a town marked by prejudice.

The scene where Scout stands in Boo Radley’s shoes resonates as a symbol of empathy and her burgeoning understanding of others’ perspectives. As she befriends Boo, the knothole gifts encapsulate the power of human connection, illustrating the profound impact of compassion in bridging divisions.

The journey of Jem home after his arm’s injury serves as a symbol of his transition from youthful innocence to the stark reality of prejudice and injustice. Atticus’s presentation of Tom Robinson’s case showcases the symbolic gesture of his defense, representing the larger fight against societal biases.

The beginning of Jem’s gradual comprehension of societal complexities is symbolized when Jem begins to see the nuances beyond childhood perceptions.

These symbolic elements resonate with larger themes of empathy, moral growth, and societal challenges, elevating “To Kill a Mockingbird” into a timeless exploration of the human condition.

Personification

Harper Lee deftly employs personification to infuse characters and settings with added dimension. When Atticus presents Tom Robinson’s case, the courtroom is personified as a living entity, intensifying the gravity of the trial and emphasizing the societal forces at play.

The moment Jem begins to perceive the complexities of the world, the idea takes on a life of its own, capturing his gradual transition from innocence to awareness. Atticus’s tender act of carrying Jem home personifies his fatherly care, transforming it into a comforting presence.

The judge’s house is imbued with a sense of authority and formality through personification, underscoring the weighty matters discussed within. Aunt Alexandra embodies societal norms personified, as her opinions and expectations shape the Finch household.

The introduction of Dill, a boy named Dill, illustrates the whimsy of childhood and the essence of curiosity personified. The character’s dynamic with Atticus’s sister reflects personified generational differences, demonstrating the clash of values.

The comfort at Jem’s bedside personifies the warmth and support of family, providing solace in times of adversity. As the trial unfolds under a dark night, the atmosphere itself becomes a living entity, heightening the tension of the events.

Through personification, Lee adds depth and resonance to characters and settings, fostering a richer connection between readers and the story’s unfolding drama.

Hyperbole

Lee employs deliberate exaggeration or hyperbole to enhance narrative impact and underscore the characters’ emotional journeys. The notion of naming Scout as the most embarrassing thing Atticus could do is a hyperbolic statement, underscoring Scout’s fiery personality and Atticus’s wry humor.

Lee’s subtle exaggeration when she mentions the Pulitzer Prize highlights the gravity of the work, acknowledging its esteemed literary status within the context of the story.

Scout’s recognition of Atticus as a humble man who “could do nothing” serves as hyperbole, highlighting the challenges she faces in reconciling her father’s unassuming nature with his moral stand.

The frequent exaggeration of Jem’s actions and emotions throughout the novel, especially his strong belief in the omnipotence of his father and his infatuation with his father’s legal prowess, serves to accentuate the transformation of his character from childlike innocence to a more nuanced understanding of the world.

The accusation of Tom Robinson as an “innocent man” is a poignant hyperbole that emphasizes the gross injustice that pervades society. Likewise, the notion of small gifts from Boo Radley assumes a larger-than-life significance, encapsulating the children’s fascination with the unknown.

Finally, the description of Boo as Boo’s brother, a shadowy figure, adds an air of mystery and exaggeration, aligning with the town’s legends about him.

Irony

In “To Kill a Mockingbird,” Harper Lee employs various types of irony that intricately shape the narrative’s depth and impact. Naming Scout “Jean Louise” symbolizes her independent spirit, which contradicts the conventions of gender roles in the town.

Scout recognizing Walter Cunningham’s father during the mob scene showcases situational irony, where a child’s innocent gesture diffuses a tense situation, challenging expectations.

Jem’s faith in his father’s unassailable moral compass forms dramatic irony, contrasting his naive belief with the complexities of Atticus’s moral struggle in defending Tom Robinson.

As Jem begins to comprehend the harsh realities of prejudice and injustice, his initial enthusiasm for his father’s defense of Tom Robinson introduces verbal irony, highlighting his gradual disillusionment.

Scout’s befriending of Boo Radley is marked by irony, as the town fears him while he secretly watches over the children.

Atticus’s carrying Jem home after the attack brings forth a blend of situational and dramatic irony, as he’s the moral rock of the story yet witnesses moral degradation within the town.

These instances of irony enrich “To Kill a Mockingbird,” offering readers a multi-layered exploration of perception, reality, and societal complexities, ultimately inviting reflection on the deeper themes and messages of the novel.

Juxtaposition

In “To Kill a Mockingbird,” Harper Lee skillfully employs juxtaposition to emphasize contrasts and provoke contemplation. The moment Atticus notes that the tree doesn’t look good, it serves as a powerful juxtaposition against the superficiality of appearances versus the depth of understanding. This contrast underlines the novel’s central theme of not judging based on surface impressions.

Scout’s befriending of Boo Radley offers a poignant juxtaposition between the unknown and the familiar. As Scout ventures into Boo’s mysterious world, the stark contrast highlights the transformation from fear to empathy, challenging preconceived notions.

Jem’s beginning of understanding societal complexities and racial prejudices is juxtaposed with his earlier innocence. This contrast underscores the stark reality he encounters, deepening his character development.

Atticus’s act of carrying Jem home after the traumatic event provides a striking juxtaposition between his role as a moral pillar and the vulnerable moments of the story. This contrast creates a thought-provoking scenario, revealing the multifaceted nature of his character.

Through such juxtapositions, Lee prompts readers to consider the complexities of human nature, society, and morality, fostering a deeper engagement with the narrative’s themes and messages.

Paradox

Lee features paradoxical statements and situations that delve into the complexities of the human experience. When they name Scout “Jean Louise” that represents a paradox where her formal name contrasts with her tomboyish nature, highlighting the tension between societal norms and individual identity.

When Scout recognizes her teacher’s ignorance about the Cunningham family’s circumstances, it underscores the irony of education coexisting with prejudice, revealing the paradox within the education system.

Atticus’s unwavering belief in justice, even in the face of a biased society, creates a paradox of moral conviction amidst societal hypocrisy. The courtroom scenes, where truth and justice should prevail, embody the paradox of a legal system influenced by prejudice.

Paradoxes such as these draw readers into the intricate tapestry of themes in the novel, prompting reflection on the incongruities and contradictions present in human behavior, society, and morality. They serve as vehicles for deeper exploration, contributing to the novel’s thought-provoking nature.

Allusion

In “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee, several literary and historical allusions enrich the narrative, contributing to the story’s depth and resonance. When Scout befriend Boo Radley, it echoes the themes of “Romeo and Juliet,” where love defies societal norms, paralleling the unconventional friendship between Scout and Boo.

The scene where Atticus carries Jem home mirrors the story of the Good Samaritan, symbolizing Atticus’s compassion and reinforcing the novel’s themes of empathy and kindness.

As Jem begin to confront the harsh realities of prejudice, the allusion to the story of “The Gray Ghost” becomes significant. This allusion draws a parallel between Boo Radley’s isolation and the misjudgment of the titular character in the novel, underscoring the theme of misconceptions.

Allegory

In “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee, allegorical elements resonate throughout the narrative, representing broader themes and concepts. The symbolism of the mockingbird serves as a powerful allegory for innocence and vulnerability.

Just as the mockingbird’s song is meant for enjoyment, characters like Tom Robinson and Boo Radley are harmed despite their benevolent nature, underscoring the unjust treatment of the pure-hearted.

The Radley house functions as an allegory for the unknown and misunderstood. Its ominous presence in the neighborhood symbolizes societal fears and biases, much like the societal fears surrounding Boo Radley.

These allegorical elements layer the narrative with deeper meanings, inviting readers to contemplate the broader implications of innocence, prejudice, and morality, contributing to the timeless resonance of the novel.

Ekphrasis

The literary device of ekphrasis is exemplified through Scout’s description of Jem’s snowman during Miss Maudie’s fire. The vivid portrayal of the snowman, fashioned to resemble the disliked Mr. Avery, serves as a striking visual within the narrative.

This ekphrasis not only provides a moment of comic relief amidst the seriousness of the events but also encapsulates the town’s tendency to judge and caricature individuals based on appearances.

Scout’s meticulous detailing of the snowman’s pipe and hat not only paints a clear mental picture but also mirrors the town’s habit of constructing elaborate personas based on limited information.

Miss Maudie’s reaction to the snowman’s demise, suggesting it was a “sin to kill a mockingbird,” reinforces the underlying message of innocence and harmlessness—themes woven throughout the novel.

Through this instance of ekphrasis, Harper Lee uses visual description to comment on the superficial judgments that pervade Maycomb’s society.

Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeic words effectively infuse the narrative with auditory dimensions, enriching the reader’s engagement with the story’s events and emotions. During the fire scene at Miss Maudie’s house, the sizzle of wood as it catches fire is described as a distinct “fizz.”

This onomatopoeic choice vividly captures the intensity of the flames and the crackling sound of burning wood, heightening the scene’s sensory impact.

Likewise, the clatter of a roly-poly captured under Scout’s bed enhances the moment’s tension and surprise, enveloping readers in the experience of the unexpected discovery.

These onomatopoeic words create an auditory atmosphere that allows readers to immerse themselves fully in the scenes, fostering a deeper connection with the characters and their surroundings. By evoking sound through language, Lee adds layers to the narrative, making the story more dynamic, visceral, and resonant for readers.

Puns

In “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee, puns subtly weave through the narrative, adding layers of meaning and moments of humor. One notable instance is the clever wordplay involving Scout’s name.

Beyond being her moniker, the term “scout” embodies her role as a keen observer, exploring the intricacies of the world around her. This pun highlights her curiosity and the novel’s emphasis on understanding and empathy.

Atticus’s comment on the Cunninghams not taking “anything they can’t pay back” showcases a playful double meaning. Beyond their surname, this pun underscores the Cunninghams’ integrity and the value they place on honor, while also eliciting a lighthearted chuckle from readers.

These puns add a touch of levity to the story, providing moments of relief amid weighty themes. However, they are not merely humorous diversions; they carry subtle messages that enrich characterizations and themes.

Repetition

Repetition in “To Kill a Mockingbird” serves as a powerful tool in reinforcing themes and evoking emotional impact. The frequent reference to “mockingbirds” underscores the central message of innocence and the importance of protecting it. The repetition of the word “nigger” throughout the dialogue starkly highlights racial prejudice and societal attitudes.

Additionally, Atticus’s repetition of “it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird” resonates throughout the novel, serving as a moral refrain that underlines the wrongful harm done to innocent individuals like Tom Robinson and Boo Radley. This repetition solidifies the novel’s core themes and amplifies its emotional resonance, making it an effective and poignant narrative technique.

The Use of Dialogue

In “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee, dialogue serves as a potent tool for character portrayal, theme exploration, and narrative tension. Through conversations, readers gain insight into characters like Atticus Finch, whose wise and empathetic dialogues exemplify his moral compass.

Dialogue also illuminates racial prejudices, highlighting the societal challenges faced by African Americans like Calpurnia. Moreover, exchanges between Scout and Jem capture the essence of sibling dynamics, further enriching the story’s emotional landscape.

Word Play

“To Kill a Mockingbird” employs wordplay techniques like puns and double entendre to layer its narrative. Scout’s name, both as a moniker and a role, showcases wordplay, reflecting her curiosity as a scout exploring her world. The Cunninghams’ name doubles as a signifier of their values.

Atticus’s reference to “nigger-lover” presents the dual impact of derogatory language and his stand against prejudice. This wordplay enriches characterization and theme, crafting a multi-dimensional narrative.

Parallelism

In “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee, instances of parallelism contribute to the novel’s structure and message. Notably, Atticus’s recurring advice to Scout and Jem, “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view,” emphasizes empathy.

This parallel structure underscores the importance of perspective and understanding in combating prejudice, fostering a central theme of compassion.

Rhetorical Devices

Harper Lee employs rhetorical devices for persuasive effect in “To Kill a Mockingbird.” Atticus’s rhetorical question, “Do you think I could face my children otherwise?” compellingly challenges Maycomb’s biased beliefs.

The repetition of “mockingbird” serves as both a metaphor and a persuasive motif, reinforcing the novel’s central moral argument against harming innocence. These rhetorical devices lend emotional weight to the narrative, encouraging readers to critically reflect on societal norms and individual responsibility.

To Kill a Mockingbird: FAQs

Other Notable Works by Harper Lee

If you are interested in “To Kill a Mockingbird,” you may also enjoy other works by or relating to Harper Lee, including:

“Go Set a Watchman”

A later-discovered manuscript, this novel explores Scout’s return to her hometown, tackling issues of racial and societal changes.

“Mockingbird Songs: My Friendship with Harper Lee”

A memoir by Wayne Flynt, shedding light on his friendship with Harper Lee and her personal life.

These additional works provide a deeper understanding of Harper Lee’s literary legacy, shedding light on her creative range and the themes that fascinated her.

Summing up: To Kill a Mockingbird: Summary, Plot & More

“To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee is a resonant masterpiece that probes societal injustices and human morality through Scout’s journey.

The rich tapestry of characters, including Atticus and Boo Radley, reflects the intricacies of humanity. Employing devices like allegory and onomatopoeia, Lee crafts a narrative that both engages and challenges.

The interplay of irony, symbolism, and allusion deepens the story’s impact. Through its enduring themes of empathy and justice, the novel invites reflection on our world’s complexities. “To Kill a Mockingbird” remains a poignant exploration of human nature and a beacon of timeless wisdom.