The Poisonwood Bible: Summary, Plot, Characters, Literary Analysis & More

“The Poisonwood Bible” is a novel by Barbara Kingsolver, first published in 1998. The novel was one of Kingsolver’s greatest critical and popular successes.

“The Poisonwood Bible” tells the story of the Price family, particularly the four Price daughters, as they navigate their lives in the Belgian Congo amidst their father’s missionary pursuits and the tumultuous political and social situation of the time.

The novel addresses themes of colonialism, cultural clash, family dynamics, and personal growth.

"The Poisonwood Bible" provides evocative language, rich symbolism, and exploration of historical and cultural contexts

Table of Contents

Summary The Plot Characters Key Themes Genres Language used Literary devices Summing upThe Plot

In “The Poisonwood Bible,” Nathan Price, a Baptist missionary, stubbornly imposes his beliefs on the Congolese village where he moves his family.

Despite the villagers’ resistance and the harsh environment, he persists.

Tragedy strikes with Ruth May’s death, exposing the consequences of his rigid mindset.

Nathan’s relentless evangelism and the family’s struggle to adapt in the Belgian Congo create a powerful narrative, demonstrating the clash of cultures and the toll of fanaticism.

Characters

Explore the diverse cast of “The Poisonwood Bible” by Barbara Kingsolver, each contributing to the compelling narrative with distinct attributes and roles.

Nathan Price

Nathan Price, the zealous Baptist missionary, drags his family to the Belgian Congo, unwilling to adapt and refusing to comprehend the culture around him.

Ruth May

Ruth May, the youngest Price daughter, tragically succumbs to the harsh environment of the Congo, symbolizing the devastating consequences of her father’s unyielding convictions.

Orleanna Price

Orleanna Price, the submissive wife and mother, grapples with her loyalty to Nathan and her growing understanding of the Congo’s challenges, while dealing with the guilt of Ruth May’s death.

Rachel Price

Rachel Price, the eldest daughter of the Price children, epitomizes the privileged American, often vain and materialistic, yet her journey in the Congo leads to unexpected self-discovery.

Leah Price

Leah Price, the twin of Adah, evolves into a fervent advocate for social justice and the Congolese people, challenging her father’s stubbornness.

Adah Price

Leah Adah and Ruth are very close. Adah overcomes her physical limitations and develops an insightful, analytical perspective on life, offering unique insights into their surroundings.

Anatole Ngemba

Anatole Ngemba, a Congolese schoolteacher, captures Leah’s heart and serves as a bridge between the Price family and the local culture, sparking important transformations.

Tata Ndu

Tata Ndu, the village chief, embodies the complexities of power in the Congo, negotiating between tradition and change while interacting with the Price family.

Brother Fowles

Brother Fowles, the former missionary, represents an alternative approach to evangelism, demonstrating a more open-minded and respectful engagement with the Congolese people.

Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Lumumba, the Congolese independence leader, symbolizes the broader political context of the time, impacting the lives of the Price family and the nation as a whole.

Mama Tataba

Mama Tataba, the village midwife, becomes a trusted friend and guide to Orleanna, offering insights into Congolese culture and providing support to the family.

Tata Kuvudundu

Tata Kuvudundu, the witch doctor, embodies the mystical and spiritual elements of the Congo, influencing the villagers’ perspectives and actions.

Eeben Axelroot

Eeben Axelroot, a charismatic pilot and smuggler, represents the ambiguous presence of Western influence in the Congo, entangled in political machinations.

Adah and Ruth May

Adah and Ruth May, the Price twins, hold distinct perspectives on the events around them; Adah’s keen observations and Ruth May’s innocence contribute unique layers to the story.

Village Children

The village children, representative of the next generation, mirror the cross-cultural interactions and exchanges in the Congo, influencing the Price sisters’ perspectives.

Key Themes

Barbara Kingsolver’s “The Poisonwood Bible” resonates with themes of cultural collision, religious zealotry, and personal metamorphosis.

Nathan refuses to embrace the Congolese culture which encapsulates the dangers of imposing one’s beliefs.

The harrowing incident of Ruth May being bitten by a snake symbolizes the clash between faith and harsh realities.

The Price women’s evolving identities in the Congo underscore the narrative’s exploration of gender roles and empowerment.

The Theme of Cultural Collision

The cultural collision is one of the central themes in the novel. The Price family’s arrival in the Congo represents a dramatic clash of Western and African cultures.

They are utterly unprepared for the challenges and complexities of life in the Congo, from the language barrier to the unfamiliar customs and traditions of the indigenous people.

This collision highlights the arrogance of Western missionaries who often fail to understand or respect the cultures they aim to convert.

The Theme of Religious Zealotry

The novel explores the theme of religious zealotry primarily through the character of Nathan Price, the patriarch of the family.

He is a fire-and-brimstone preacher who is unwavering in his belief that he has been called by God to convert the Congolese people to Christianity.

His fervor blinds him to the realities of the world around him, and he becomes increasingly obsessed with his mission.

Nathan’s religious zealotry serves as a critique of religious extremism and the dangers of imposing one’s beliefs on others without understanding or empathy.

His rigid faith ultimately alienates him from his family and the Congolese people, highlighting the destructive nature of fanaticism.

The Theme of Personal Metamorphosis

Throughout the novel, each of the Price daughters undergoes a significant personal metamorphosis.

They arrive in the Congo with their own preconceived notions and attitudes, but their experiences in Africa force them to reevaluate their beliefs and values.

Characters like Rachel, Leah, Adah, and Ruth May experience personal growth and transformation as they confront the challenges of the Congo.

They learn to adapt to the environment, understand the culture, and question the dogmas they were raised with.

Adah, in particular, undergoes a profound metamorphosis, embracing her unique perspective on language and life, which reflects the novel’s theme of personal transformation and the idea that individuality and self-discovery can lead to personal enlightenment.

Genres in The Poisonwood Bible

“The Poisonwood Bible” is a historical fiction novel interwoven with family drama and a profound coming-of-age narrative.

These genres synergize, enabling the portrayal of historical events as catalysts for individual and collective growth.

The familial dynamics mirror broader societal shifts, lending depth and relatability to the characters’ journeys.

Language used in The Poisonwood Bible

Barbara Kingsolver employs eloquent prose in “The Poisonwood Bible” to vividly encapsulate the Congo’s exotic ambiance and the characters’ complex emotions.

Her descriptive prowess immerses readers in the verdant jungles, while also evoking the Price family’s struggles and triumphs.

The language becomes a conduit for readers to experience the tension, hope, and anguish that define the characters’ lives.

Literary devices in The Poisonwood Bible

In “The Poisonwood Bible,” Barbara Kingsolver adeptly wields literary devices to enrich the narrative.

Symbolism thrives in elements like Nathan’s unbending demeanor, representative of colonial arrogance. Metaphors, like Ruth May’s snakebite, underscore spiritual and physical danger.

The multiperspective narrative enhances our insight into each Price daughter’s transformative journey.

These devices converge, illuminating the novel’s exploration of faith, identity, and the consequences of cultural imposition.

Similes

Barbara Kingsolver employs vivid similes throughout “The Poisonwood Bible” to enhance imagery and engagement. For instance, when describing the Price women’s transition, their evolution is likened to “butterflies emerging from chrysalises.”

This simile visualizes their growth, mirroring their metamorphosis amidst the harsh Congo landscape and adding depth to their journeys.

Metaphors

The Price women (with four daughters) symbolize a modern-day discipleship with each sister embodying a facet of their father’s misguided religious fervor, reflecting the complexities of faith. “Jesus Christ” serves as a metaphor, illustrating Nathan’s imposing presence.

The “poisonwood tree” signifies the invasive impact of colonialism.

These metaphors delve beyond literal interpretations, facilitating a nuanced exploration of the characters’ roles and the broader themes of the novel.

Analogies

The journey of the Price women, akin to a poisonwood bible study guide, unveils layers of faith, womanhood, and autonomy.

Leah’s evolution paralleled to a young girl finding her voice in unfamiliar terrain, facilitates a deeper understanding of personal growth within the tumultuous Congo environment.

Imagery

The chicken coop becomes a metaphorical prison for the Price women, symbolizing their entrapment in a foreign land. When Leah marries Anatole the act paints a mental picture of unity amidst cultural diversity.

The imagery of the remaining Price sisters fosters a poignant sense of connection amid their diverse paths. Reverend Price’s presence, conjured through descriptive imagery, embodies a zealous and domineering force.

Symbolism

The village witch doctor symbolizes the enigmatic spiritual connection between the villagers and their land.

The French Congo represents the colonial legacy, reflecting the destructive impact of outside forces on native cultures.

The evil sign serves as a metaphor for the ominous consequences of cultural imposition by the missionary family. The “Price girls” symbolize the diverse reactions to adversity, embodying resilience, growth, and defiance.

Personification

The “bond group entertainment,” personified, becomes a source of both amusement and cultural awareness.

Instances like the village witch doctor and the evil sign taking on human attributes deepen the connection between the physical world and the characters’ perceptions, enhancing the reader’s engagement with the narrative.

Hyperbole

Exaggerated descriptions, such as “Leah learns about a thousand things in a heartbeat,” magnify the intensity of her experiences and swift understanding, contributing to the narrative’s emotional resonance.

Irony

The irony in Leah’s determination to be a progressive force, and when she and Anatole marry embodiments tradition, adds complexity to her character.

The village elders seeking guidance from the Price family, often unknowingly, introduce situational irony.

The irony in Adah’s physical limitations, yet sharp insights, and Rachel’s ambition contrasted with her naivety, amplify character depth.

Juxtaposition

The abrupt transition from Ruth May’s innocence to her tragic demise, resulting from a snakebite, creates a powerful juxtaposition between life and death.

Similarly, as Leah begins her journey to social awareness, her growth stands in juxtaposition to her initial innocence, shedding light on the complexities of her evolution amidst the challenges of the Congo.

Paradox

The statement “It bites Ruth May, and she dies” encapsulates the profound irony of life’s fragility in the Congo, starkly contrasting her father Reverend Price’s pursuit of salvation.

The paradox of “twin Adah” manifests in her physical limitations yet exceptional perceptiveness, echoing the complexity of human potential and the duality of her existence.

Allusion

Barbara Kingsolver employs allusions in “The Poisonwood Bible” to connect with historical and literary contexts.

The reference to Tata Jesus subtly alludes to the blend of indigenous beliefs and Christianity in the Congo. The allegorical nature of “Anatole argues” hints at broader societal clashes, reflecting the tensions of the time.

Allegory

The demonstration garden serves as an allegory for the Price family’s attempt to cultivate change amidst adversity. The poisonous snakes symbolize the dangers lurking beneath seemingly benign surfaces.

The progression of “Rachel, Leah, Adah” metaphorically illustrates stages of understanding and growth, forming an allegorical journey mirroring the Congo’s challenges and rewards.

Ekphrasis

While not overtly describing visual art, the vivid portrayal of the angry villagers, visually engaging, illustrates their collective emotions.

The mission league serves as a symbol of imposed ideals, resembling a canvas of Western influence on African soil.

The vivid depiction of “Father’s sermons” conveys their impact, akin to brushstrokes that shape beliefs. Adah’s twin, described uniquely, takes on a form of verbal portraiture.

Onomatopoeia

Barbara Kingsolver employs onomatopoeic words to immerse readers in auditory experiences.

The sounds of bustling markets in Africa and the tranquil landscapes of Georgia come alive through descriptive language, enriching the narrative’s sensory texture.

Repetition

The consistent reference to “Reverend Price” emphasizes his unyielding nature and the impact of his actions on the family.

The repetition of “Rachel runs away” serves as a motif, symbolizing her inclination to escape challenges, reflecting her superficial nature and her struggles within the Congo’s harsh realities.

The Use of Dialogue

Conversations with the “live-in helper” offer glimpses into the Congolese perspective, enriching the narrative’s cultural exploration.

The dialogue between the sisters, presented through a distinct “narrative form,” provides insight into their diverse journeys.

Additionally, interactions with “Nelson” showcase the complexities of identity and relationships within the tumultuous Congo setting.

Word Play

Barbara Kingsolver weaves wordplay into “The Poisonwood Bible,” employing puns and double entendres to layer meaning.

For instance, when Nathan refuses that shows (symbolizes) his stubbornness, while his four daughters convey both their bond and the burden of his expectations. The tragic irony lies in “Ruth May,” echoing innocence.

Additionally, the sisters’ names, “Rachel,” and “Leah,” subtly reflect their evolving identities, enhancing character depth. Adah’s return contains wordplay, signifying her reappearance and transformation.

Parallelism

Instances like the political situation, Congolese people, and Africa interweave, emphasizing interconnected themes.

The repetition of daughters, Nelson, and Adah’s return enhances their transformative arcs. The recurrence of Congo, death, lives, and story underscores central themes, capturing the intricacies of life in the Congo.

Rhetorical Devices

Kingsolver strategically deploys rhetorical devices for persuasion and engagement. Contrasting Africa with Georgia emphasizes cultural differences.

Utilizing narrative form guides the reader’s perspective. Mother’s portrayal intertwines with themes of sacrifice.

Exploration of Christianity delves into the characters’ beliefs. The prominence of Anatole highlights social and cultural dimensions.

The repeated emphasis on Congo underscores its significance. The repetition of death lives, and the story reinforces narrative weight and purpose.

The Poisonwood Bible: FAQs

In this section, get answers to questions about Barbara Kingsolver’s captivating novel. Delve into key themes, characters, and more.

Who are the members of the Price family?

The Price family includes Nathan, a fervent missionary; Orleanna, his wife; and their four daughters: Rachel, Leah, Adah, and Ruth May. Each daughter represents unique perspectives and growth.

What impact does Ruth May’s death have in The Poisonwood Bible?

Ruth May’s death from a snakebite serves as a turning point, illuminating the clash between faith and reality. Her loss deeply affects each family member, catalyzing their individual journeys.

What happens when Nathan refuses to stop with religious talk?

Nathan’s refusal to adapt deepens cultural rifts, leading to conflict and isolation. His relentless religious zeal drives the family further apart, exacerbating their struggles in the Congo.

What is the message that The Poisonwood Bible sends?

“The Poisonwood Bible” explores the dangers of cultural imposition and religious fanaticism while highlighting the resilience of individuals facing adversity. It showcases personal growth, identity, and the impact of historical events.

Summing up: The Poisonwood Bible: Summary, Plot & More

In “The Poisonwood Bible,” Barbara Kingsolver masterfully crafts a narrative that delves into the clash of cultures, the consequences of fanaticism, and the transformative power of personal growth.

Through vivid characters like the Price women and skillful use of literary techniques, Kingsolver weaves a tapestry of themes encompassing faith, identity, and colonialism.

The novel’s evocative language, rich symbolism, and exploration of historical and cultural contexts make it a thought-provoking and impactful read, resonating with readers long after the final page.

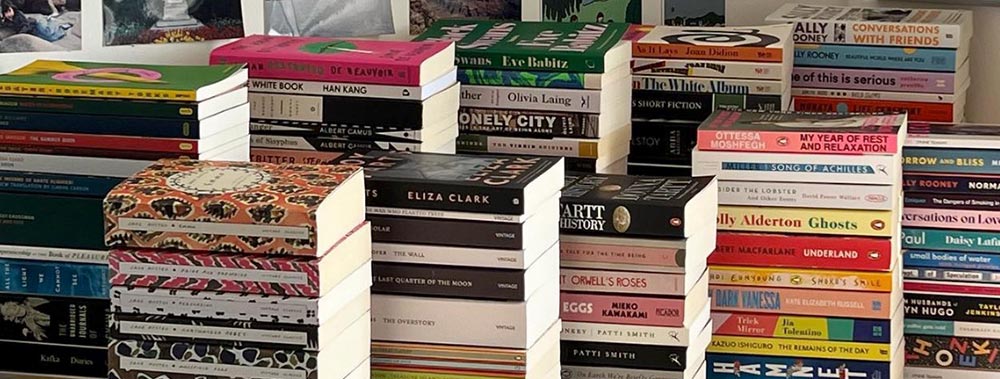

Other Notable Works by Barbara Kingsolver

If you enjoyed “The Poisonwood Bible,” you might also appreciate other works by Barbara Kingsolver:

- “The Bean Trees”

- “Animal Dreams”

- “Prodigal Summer”

- “The Lacuna”

- “Flight Behavior”

- “The Prodigal Daughter” (sequel to “The Poisonwood Bible”)

These works showcase Kingsolver’s remarkable storytelling and exploration of various themes, offering a diverse range of narratives that captivate readers with their depth and complexity.