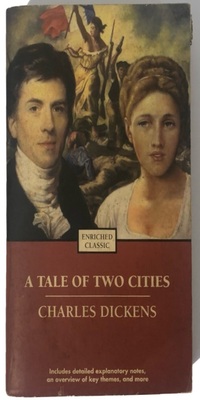

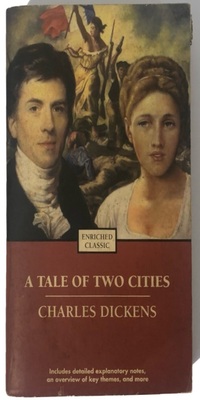

A Tale of Two Cities: Summary, Plot, Characters, Literary Analysis & More

“A Tale of Two Cities” is a historical novel by Charles Dickens, initially published in 1859.

Regarded as one of Dickens’ most celebrated and impactful works, the novel delves into the tumultuous backdrop of the French Revolution.

It intertwines the fates of Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton, central characters whose lives epitomize the complex interplay of love, sacrifice, and societal upheaval.

Set against the backdrop of Paris and London, the narrative navigates the stark contrast between these two cities, illuminating the stark disparities in social class and human worth.

As the court acquits Darnay, a former English spy, for his alleged involvement with his uncle’s controversial legacy, Dickens masterfully weaves a tale that delves deep into themes of justice, sacrifice, and personal redemption amidst the chaotic milieu of revolutionary France.

A Tale of Two Cities: Dickens' transcends its historical setting, offering timeless reflections on societal injustices and personal redemption.

Table of Contents

Summary The Plot Characters Key Themes Genres Language used Literary devices Summing upThe Plot

In “A Tale of Two Cities” summary you will see that the story revolves around the intertwined lives of several characters during the tumultuous French Revolution.

Dr. Manette, once unjustly imprisoned, is reunited with his daughter Lucie in London.

Lucie finds herself entangled in a love triangle with the virtuous Charles Darnay and the dissolute Sydney Carton, who finds purpose in his selfless affection for her.

The novel navigates their struggles amidst the chaos, with the vengeful Madame Defarge knitting a record of injustices.

As events unfold, Darnay is ensnared in the revolution’s turmoil, leading to Carton’s ultimate act of self-sacrifice, exchanging his life for Darnay’s, and finding redemption in the process.

Characters

A vivid tapestry of characters comes to life against the tumultuous backdrop of the French Revolution and its impact on both London and Paris.

From the resolute and enigmatic figure of Sydney Carton to the indomitable Lucie Manette, the novel weaves a complex web of relationships that mirror the stark contrasts between personal struggles and the sweeping forces of history.

Each character’s journey intertwines with the revolutionary fervor of the time, shedding light on the resilience of the human spirit amidst chaos and sacrifice.

In this exploration of the “Characters” section, we delve into the diverse cast that populates Dickens’ gripping tale, each individual contributing a unique thread to the rich narrative fabric.

Sydney Carton

Sydney Carton, a complex and tormented figure, is introduced as a disillusioned lawyer with a penchant for alcohol.

However, his innate goodness is revealed through his unrequited love for Lucie Manette, which drives him to a heroic act of self-sacrifice.

The transformation of Carton from a dissolute cynic to a symbol of redemption is one of the novel’s most poignant arcs.

Doctor Manette

Doctor Manette, once unjustly imprisoned for eighteen years, is the quintessential victim of societal injustice.

His journey of recovery, guided by his daughter Lucie, showcases his resilience and inherent goodness.

The doctor’s struggles and his eventual strength to face his traumatic past play a vital role in the story’s unfolding.

Lucie Manette

Lucie Manette embodies purity and compassion.

Reunited with her father after his long imprisonment, she becomes a beacon of hope for those around her, captivating the hearts of both Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton.

Her unwavering kindness and devotion act as a stabilizing force amidst the chaos of revolutionary France.

Madame Defarge

Madame Thérèse Defarge, seemingly a quiet knitting shopkeeper, conceals a vengeful and ruthless nature.

As a fervent participant in the revolution, she relentlessly seeks retribution for her family’s suffering at the hands of the aristocracy.

Her vengeful determination and knitting of the infamous “register” underscore the novel’s themes of revenge and the cyclical nature of violence.

In “A Tale of Two Cities,” these characters personify the complexities of human nature and the transformative power of personal choices against the backdrop of societal upheaval.

Key Themes

Dickens weaves an intricate tapestry of themes that resonate throughout “A Tale of Two Cities.”

The duality of existence is a central motif, mirrored in the contrasting settings of London and Paris.

The French Revolution underscores the consequences of societal injustice and the unquenchable thirst for vengeance.

As Charles Darnay’s lineage connects him to the brutality of the aristocracy, the novel explores the cyclical nature of violence and the potential for personal redemption.

The revolutionary fervor, embodied by the character of Madame Defarge, highlights the ever-present tension between oppressed and oppressor, mirroring historical struggles.

Genres in A Tale of Two Cities

“A Tale of Two Cities” defies easy categorization, embracing elements of historical fiction and literary romance.

The backdrop of the French Revolution lends the story historical authenticity, while personal relationships between characters like Sydney Carton and Lucie Manette infuse it with romantic undertones.

This blending of genres allows Dickens to explore both grand historical events and intimate human emotions, creating a narrative that appeals to readers on multiple levels.

Language used in A Tale of Two Cities

Dickens employs a vivid and evocative language style to transport readers to the tumultuous period of the French Revolution.

Through meticulously chosen phrases, he captures the stark contrast between the “best of times” and the “worst of times” in both London and Paris.

The revolutionary fervor, symbolized by the bloodthirsty crowd in Saint Antoine, is palpable through Dickens’ descriptive prose.

The language mirrors the tension, desperation, and fervor of the era, all while carrying emotional weight that adds depth to characters like Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton, even as they confront their own inner struggles.

Literary devices in A Tale of Two Cities

Charles Dickens employs a masterful array of literary devices that enrich the narrative’s depth and impact.

Through vivid imagery, he conjures detailed scenes, enabling readers to immerse themselves in the world of the novel.

The story exemplifies the historical and allegorical genres, intertwining characters and events with broader themes of societal upheaval and personal redemption.

Dickens artfully employs foreshadowing to heighten suspense and dramatic irony, while irony, symbolism, and social commentary reveal the complexities of the French Revolution’s turmoil and the characters’ moral dilemmas.

His skillful use of wordplay, allusions, and symbolism further enhance the multifaceted nature of the story, showcasing Dickens’ narrative prowess.

Similes

When Lucie approaches her father, her tenderness is likened to “the footprints on a soft sea shore.”

This simile not only conveys her gentle nature but also emphasizes the fragility of their relationship in the midst of turmoil. Similarly, the description of Darnay’s guilt “hanging like a ghost at the back of his conscience” captures the haunting nature of his inner turmoil, enhancing reader empathy and comprehension.

Metaphors

Dickens utilizes metaphors to convey deeper meanings and complexities. Carton’s confession, “I am the resurrection and the life,” reflects his transformation from a life of despair to one of purposeful sacrifice, mirroring spiritual rebirth.

The peasant girl’s knitting, symbolic of Madame Defarge’s vindictive registry, metaphorically weaves the threads of revolution and vengeance.

The garret room, resembling a “wild beast’s den,” metaphorically represents Dr. Manette’s psychological imprisonment and foreshadows his resurfacing trauma.

Dickens’ metaphors enrich character depth and thematic exploration, inviting readers to delve into the layers of the story’s significance.

Analogies

The analogy of Darnay’s uncle as a spider, weaving a web that entangles innocents like Darnay, vividly portrays his malevolent influence.

The act of rescuing Darnay ( there is even a fight to fight to rescue Darnay) parallels a journey from darkness to light, akin to escaping the clutches of a dungeon.

These analogies convey complex themes of manipulation and salvation in an accessible manner, enabling readers to grasp the depth of characters’ struggles and the overarching societal turmoil within the French Revolution.

Imagery

The description when Barsad carry Darnay conjures an image of a burdened figure, symbolizing the weight of his destiny.

As Darnay receives his verdict, Dickens paints a detailed picture, engaging readers’ empathy in this pivotal moment.

The portrayal of Jerry Cruncher as a “resurrection man” evokes a visceral image, capturing the eerie nature of his occupation.

These instances of imagery bring the story’s world and characters to life, creating vivid sensory experiences for readers.

Symbolism

The shattered wine cask outside the wine shop becomes a vivid emblem of the downtrodden French peasantry, foreshadowing their uprising.

The unforgiving grindstone, personifying Madame Defarge’s unrelenting vengeance, grinds away at the oppressive aristocracy.

The Marquis St. Evrémonde’s carriage, trampling a child in its path, serves as a chilling symbol of aristocratic cruelty.

These symbols, intricately woven into the storyline, amplify themes of social injustice and tyranny’s consequences, underscoring the depth and resonance of Dickens’ storytelling.

Personification

When Jarvis Lorry proclaims “Recalled to Life,” the phrase takes on a human quality, foreshadowing characters like Dr. Manette’s revival. Dr. Manette’s relapse, described as a “reversion to a state of nature,” personifies his descent into a primal psychological realm.

The marriage of Lucie Manette to Charles Darnay embodies hope and rejuvenation, personifying the revival of life’s joys. These personifications add layers to characters and settings, illuminating emotional dimensions and enhancing the narrative’s impact.

Hyperbole

Hyperbole serves as a powerful literary device.

The relapse of Dr. Manette (Dr. Manette relapses into his shoe-making madness), described as a return to a “wildness and bestiality,” employs hyperbole to emphasize the extent of his psychological turmoil.

Charles Darnay’s willingness to endure “a thousand daggers” to marry Lucie is an exaggeration that underscores his deep love and determination.

The depiction of Darnay’s father as a “monster and a coward,” though an exaggeration, highlights the horrors perpetuated by the aristocracy.

These instances of hyperbole magnify emotions, heighten dramatic tension, and underscore the novel’s themes of sacrifice, love, and societal critique.

Irony

In “A Tale of Two Cities,” irony takes on various forms, enriching the narrative’s complexity.

The unexpected resurrection of Roger Cly, a presumed dead character, is a prime example of situational irony, as it defies expectations and adds suspense.

Sydney Carton’s arrangement to switch places with Charles Darnay, a plan born out of self-disdain, showcases dramatic irony, as readers know his ultimate fate.

The presence of a French spy within the Defarges’ midst constitutes dramatic irony as well, heightening tension.

Ernest Defarge’s initial appearance as a loyal wine shop owner, while he is part of the revolutionary cause, introduces verbal irony, adding layers to character dynamics and plot twists.

Juxtaposition

Charles Dickens employs juxtaposition masterfully in “A Tale of Two Cities” to underline stark contrasts and evoke contemplation.

The initial setting of London and Paris, disparate yet intertwined, highlights social inequalities.

The personal struggle within Sydney Carton, who arranges Darnay’s fate, mirrors the external turmoil of the French Revolution.

The apparent benevolence of Ernest Defarge juxtaposed with his revolutionary zeal underscores complex character motivations.

Dickens uses these juxtapositions to amplify the novel’s themes of duality, sacrifice, and societal upheaval.

Paradox

Paradoxes abound in the novel, enriching its narrative. Sydney Carton’s self-deprecating statement, “It is a far, far better thing that I do,” just before his sacrificial death, presents a paradox of life found through death.

Carton’s ultimate sacrifice is paradoxically a means of personal redemption. His death becomes an act of renewal, echoing larger themes of resurrection within the story.

These paradoxes add layers of meaning, underscoring the novel’s exploration of transformation and the intertwined nature of life and death.

Allegory

While not a pure allegory, “A Tale of Two Cities” does contain allegorical elements that symbolize broader themes. Sydney Carton’s self-sacrifice, where Carton arranges to switch places with Charles Darnay in Darnay’s cell, serves as a metaphorical representation of resurrection and personal transformation.

This sacrifice allegorically echoes themes of redemption and the power of selflessness. While the novel isn’t exclusively allegorical, these elements contribute to its layered exploration of human nature, sacrifice, and societal change amidst the tumultuous backdrop of the French Revolution.

Ekphrasis

“A Tale of Two Cities” contains instances of ekphrasis, vividly depicting art within the narrative.

Defarge’s wine shop, a hub of revolutionary activity, becomes a visual centerpiece symbolizing the fervor for change.

The portrayal of the close bond between Lucie and her father, Dr. Manette, forms an emotional canvas of their relationship’s depth. Jarvis Lorry’s travels between England and France paint a mental picture of the physical and emotional journeys undertaken.

While not explicitly an ekphrasis, the depiction of England serves as a backdrop that enriches the reader’s mental imagery. These descriptions enhance the story’s atmosphere and character dynamics.

Repetition

The phrase “Lorry travels” emphasizes Jarvis Lorry’s frequent movement, highlighting his pivotal role in connecting England and France.

The repetition of “England” serves as a reminder of the story’s varied settings and their significance. The mention of the former servant, coupled with the imagery of the “husband’s life,” accentuates the struggle and sacrifices experienced by various characters.

These repetitions echo throughout the narrative, creating a rhythmic effect that reinforces themes of interconnectedness and personal transformation.

The Use of Dialogue

The pivotal scene where Carton confesses his intent to switch places with Darnay is charged with emotional weight, revealing his inner turmoil and sacrificial nature through candid conversation.

Similarly, the dialogue where Carton explains his plan, “Once inside the cell, he drugs Darnay and takes his place,” intricately weaves tension and suspense, setting the stage for a dramatic turn of events.

Through dialogue, Dickens deftly deepens character complexities, enriches themes, and keeps readers engaged in the unfolding narrative.

Word Play

The ominous arrival of Madame Defarge (Madame Defarge arrives suddenly at the Manettes’ former Paris residence) intertwines wordplay and foreshadowing, as her knitting conceals not only her vengeful record but also the impending revolution’s woven fate.

The term “peasant girl” encapsulates both a socio-economic status and, ironically, hints at the future role of the girl in the story’s tumultuous events.

The epithet “cruel marquis” employs both descriptive language and evocative word choice to emphasize the oppressive nature of the aristocracy.

Through these linguistic layers, Dickens adds depth and complexity, engaging readers on multiple levels.

Parallelism

Miss Pross’ resolute dedication to Lucie Manette and the golden hair she lovingly cherishes creates a poignant parallel.

The theme of imprisonment resonates through Dover, symbolizing the physical and emotional barriers characters face. The “frozen deep” of social injustice and the aristocracy’s oppressive power parallel the “frozen deep” of the Dover cliffs, emphasizing the entrapment of individuals within a larger system.

The poignant image of “making shoes” at the Evrémonde estate mirrors the cycle of violence, emphasizing the story’s themes of fate and retribution.

Rhetorical Devices

Rhetorical devices are deftly employed in “A Tale of Two Cities” to accentuate persuasive impact. The question “Was it the light of France?” at the onset of the French Revolution begins invokes introspection and foreshadows the upheaval to follow.

Lucie’s apartment, a symbol of sanctuary, serves as a powerful backdrop for Carton’s rhetorical declaration, “It is a far, far better thing that I do.” This device imparts emotional resonance and emphasizes his ultimate sacrifice.

The parallelism in Sydney Carton’s famous line, “Are there no prisons? Are there no workhouses?” merges rhetoric with social commentary, compelling readers to reflect on societal inequities.

A Tale of Two Cities: FAQs

As readers traverse the intricate streets of London and Paris during the tumultuous French Revolution, questions inevitably arise about the characters, themes, and historical context that shape this gripping narrative.

Delving into these frequently asked questions allows us to unravel the layers of mystery, sacrifice, and redemption that define the novel.

What is the summary of A Tale of Two Cities?

“A Tale of Two Cities” is set during the French Revolution, intertwining the lives of various characters in Paris and London. It follows Charles Darnay, who faces danger due to his aristocratic connections, and Sydney Carton, who redeems himself through a selfless sacrifice.

What is the moral of the tale of two cities?

The novel underscores the transformative power of sacrifice and redemption. It portrays how individuals can rise above their pasts and find redemption by making selfless choices, echoing the sentiment that even in the darkest of times, humanity can shine through.

What is the main theme of A Tale of Two Cities?

The primary theme is duality, showcasing the stark contrast between different social classes, nations, and personal choices. It delves into the dual nature of human experience, where love and sacrifice coexist with oppression and injustice.

Is A Tale of Two Cities hard to read?

The novel’s intricate language and historical context might pose some challenges, but its compelling narrative and timeless themes make it accessible with careful reading. The depth of characters and themes rewards the effort.

What role does Charles Darnay play in “A Tale of Two Cities”?

Charles Darnay is a central character, an aristocrat who renounces his family’s oppressive ways. He embodies the theme of personal transformation, advocating for justice and equality, and becoming a symbol of hope for a better future amidst the turbulence of the French Revolution.

Summing up: A Tale of Two Cities: Summary, Plot & More

As you can see from this “A Tale of Two Cities” summary, this famous work by Charles Dickens is an epic tapestry interwoven with characters and events that embody the turbulence of revolutionary France and the contrasting tranquility of London.

Through the captivating narrative, Dickens masterfully unveils the stark dualities of society, the complexities of human nature, and the enduring power of sacrifice.

The dramatic moments, such as Defarge producing the hidden letter or Miss Pross facing danger armed with her own gun, leave indelible impressions.

With its rich symbolism, engaging dialogues, and carefully crafted themes, the novel transcends its historical setting, offering timeless reflections on societal injustices and personal redemption.

The poignant climax of Sydney Carton’s ultimate sacrifice echoes through the ages, resonating with readers as a testament to love, selflessness, and the potential for transformation even within the darkest of times.

“A Tale of Two Cities” continues to captivate and inspire generations, inviting them to delve into the intricacies of human emotions and societal evolution.

Other Notable Works by Charles Dickens

If you are interested in Great Expectations, you may be interested in other works by Charles Dickens including:

- Great Expectations: Follow the journey of young Pip as he navigates social class, love, and personal growth in Victorian England, while encountering enigmatic characters like Miss Havisham and the convict Magwitch.

- Oliver Twist: Dive into the harsh realities of 19th-century London as the orphaned Oliver Twist faces adversity and seeks a better life, revealing the underbelly of society through characters like the cunning Fagin and the kind-hearted Nancy.

- David Copperfield: Join David Copperfield in his coming-of-age tale, as he overcomes challenges, encounters a colorful cast of characters, and evolves into a resilient individual, mirroring aspects of Dickens’ own life.

- A Christmas Carol: Immerse yourself in this timeless Christmas classic, as Ebenezer Scrooge is transformed through visits from ghosts, learning the true spirit of giving and compassion.

Bleak House: Uncover a labyrinthine legal system and intricate family dynamics in this novel that intertwines the lives of various characters while highlighting social issues of the time. - Hard Times: Explore the contrast between utilitarianism and humanity through the lives of characters like the strict Mr. Gradgrind and the free-spirited Sissy Jupe in a town dominated by industry.

These works showcase Dickens’ unparalleled ability to capture the human experience and social commentary, making each one a captivating journey through Victorian society and its multifaceted characters.